Introduced by Wu Shanshan, artistic director of the Hao Theater via the ACC office in Taipei we visited the TaiYuan Asian Puppet Theatre Mueum (formerly known as: Lin Liu-Hsin Puppet Theatre Museum) which is now closed to the public and in the process of packing up its puppet collection, which was started by Dr. Paul Lin in the 1980’s and consists of over 10.000 artifacts. There are glove-, shadow-, rod-, and string puppets spanning from Taiwanese, Minnan (Hokkien), and Hakka puppetry to those from Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar, Indonesia, Thailand, India, Japan and more. Last year the collection has been donated to the National Taiwan Museum.

We were introduced to the still accessible parts of the collection in storage by Kim Siebert, who has been the conservator for these puppets for the past decade and who is currently part of the team that works on the collection’s transition into the museum. While Kim pulled out drawer after drawer in the dim and tight storage spaces of the former museum to show us their contents and expose us to the incredible variety of genres and the individuals within these genres, we talked about the complexities that go into holding the puppets in the state they are currently in, which is different from the space they animated, when they were held by the hands of puppeteers performing rituals and/or entertainment in temples, on village squares or at ceremonies.

Kim has worked with historical collections in Africa, the US and in Asia and her practice as a conservator emphasizes ethical collaboration and exchange with makers and performers in partnerships, respecting inherited values and techniques to the long term preservation of the material culture. Kim’s expertise and openness, her humor and her holistic approach to care for the puppets (beyond her first priority to keep them safe from physical damage or disintegration) was the base for a fascinating conversation that lasted a few hours (and has been continued since.)

We talked about repairs – and how the conservator must include in the repairs the option to “undo” them in case the need to do so arises in the future and rigorous reporting of any changes made at this stage. We touched upon the sacred space of the puppeteer. Kim told us the biography of Marshall Tian Du Yuan Shuai (田都元帅) the puppet god (or the god of the theater) and we talked about the role he plays in rituals that precede a traditional puppet performance. We talked about temple culture and temple fairs in Taiwan, and while looking at the costumes of hundreds of puppets Kim pointed out details, such as rough repair stitches on top of extremely detailed embroidery, or the integration of candy wrapper pieces for glitter effects in more recent costumes.

Most puppets lay openly on their backs, next to each other in tight rows. Their heads rested on small white cotton pillows, each one customized for each head’s shape and size. Not only did these pillows prevent the heads from rolling around and getting damaged, the respect expressed in this gesture made our heads, like those of the puppets, also a bit more comfortable. It was visible that the puppets were not only exposed, but also cared for.

As we tried to absorb the richness of the collection, we also tried to understand the value of these objects in their current state which can’t be simply separated from their former lives as performers. How does one evaluate these now retired objects/tools/artifacts, what is the actual value of preserving the tangible parts of an intangible performance heritage?

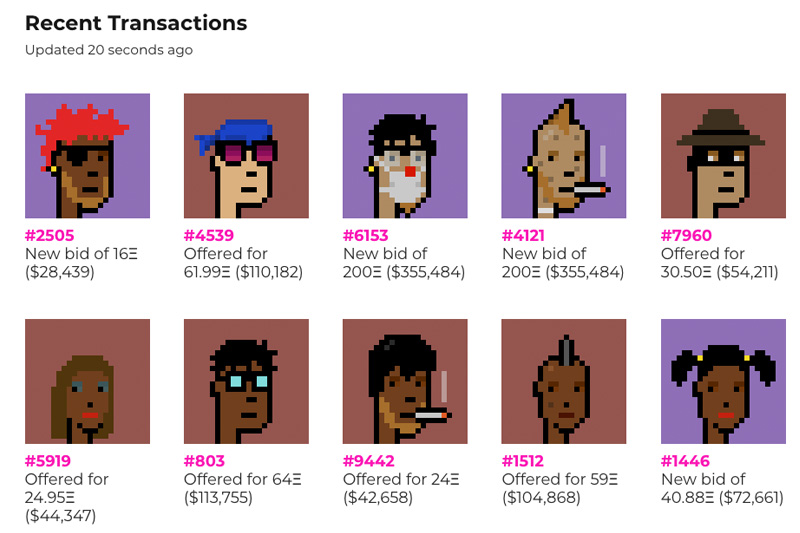

With some of these questions on our minds we returned home, opened our computers, browsed through our social media feeds and discovered that “Cryptopunk 7804,” a 24×24 pixel digital art image, had just sold for $7.5 Million Dollars. CryptoPunk 7804 is a pipe-smoking alien who wears a hat and sunglasses and is one of 10.000 “heads,” which were algorithmically generated through a computer code, developed and released by Larva Labs, a New York-based software firm, in 2017. CryptoPunk 7804’s ownership has been made digitally scarce through the use of blockchain technology and “his” value, or price, has been inflated through the latest craze on NFT imagery : digital artwork linked to a unique kind of cryptocurrency called a “non-fungible token.”

No two characters are exactly alike, but some traits are more rare than others. They were originally released for free and could be claimed by anyone with an Ethereum wallet. There will never be more than the original 10,000 CryptoPunks and all are non-fungible tokens. The value of each NFT derives from its verifiable digital ownership. No two CryptoPunks are exactly alike. None of the puppet heads we had just looked at were alike either. Like the CryptoPunks were created by algorithms – set rules – the puppet heads were created by code and properties which in the past we called traditions of identifiable characters. But how can we compare the creation in these two collections of heads?

While the 10.000 heads of these traditional storytellers are being packed up to move from the public space into the guarded storage of a museum, the 10.000 CryptoPunks step into the public limelight performing financial transactions on the Internet. Are these recorded and published financial transactions the stories we tell each other now? And if so, what’s the value that comes with these stories, and the morals, and the entertainment and what’s the price we pay for these tales?

As Michael Connor mentioned in his recent piece: “Another new world” for Rhizome: Both NFTs and the traditional art market have a significant carbon footprint. Both involve negotiable ideas about what constitute the artwork, and what constitutes ownership of it. Both involve the staking of monetary value based on reputation, perceived desirability, a good sales pitch, and more. Dynamics shaping the NFT art market are rooted in material infrastructures, politics of nation states, deep-seated societal power relations, barriers of language and access.

Similar ideas about the creation of collectibles and the maintenance of value and ownership have been stated in a co-authored paper by Rosie H.Cook, Kim Siebert, Kuo Chien-Fu and Ma Si-Yuan “Performing Puppet Conservation: Concepts of Expertise and Significance in the Conservation of Chinese Glove Puppet Costumes.” The authors write: For objects relating to performance, particularly in the context of a museum or an archive dedicated to performance art, the process is a more complex one, as the object has been collected as a document of the performance rather than as a self-contained artifact and its meaning derives from a web of human linkages and social interaction. It is therefore necessary to approach its conservation relative not to the object’s individual condition, but its capacity to “perform” in its new context, in order to document the performing art which it represents. Its value is providing different kinds of evidence, and in the preservation of the performance context.