We went back again to the Taiyuan Asian Puppet Theatre Museum and watched the art handlers packing up the collection. While last time we focused on the “performance aspect” of packing up and conservation, this time we were drawn to the “system,” specifically the system of numbers used to organize and categorize these “objects,” which could also be called “characters.” While the fingers of the accountants who kept the numbers in check slid left and right across the rows of digits on paper and pencil tips ticked them off or crossed them out, when packers had confirmed the correlating object, we thought of how our human narratives of romance, revenge, pleasure, mystery, fights and mischief these puppets once embodied, now turn into math machines can understand. Or is that thought too small in range? Isn’t doing math, counting and cross-checking numbers is also a sort of storytelling we humans enjoy and can find satisfaction and meaning in?

eteam: Why do the art packers have to handle so many numbers? I see printed out lists, handwritten lists, tags, labels…and everyone is talking in numbers to each other. What’s kind of amazing for me is that I have never been in a Chinese speaking environment where I can understand 90% of the conversation that several people are having with each other.

Kim Siebert: What the art packers are doing is really important, it’s very tedious, because each object is unique. And why two of them are doing it, in fact three of them, four of them…five. There is the person who draws up the original inventory list…there is actually six.

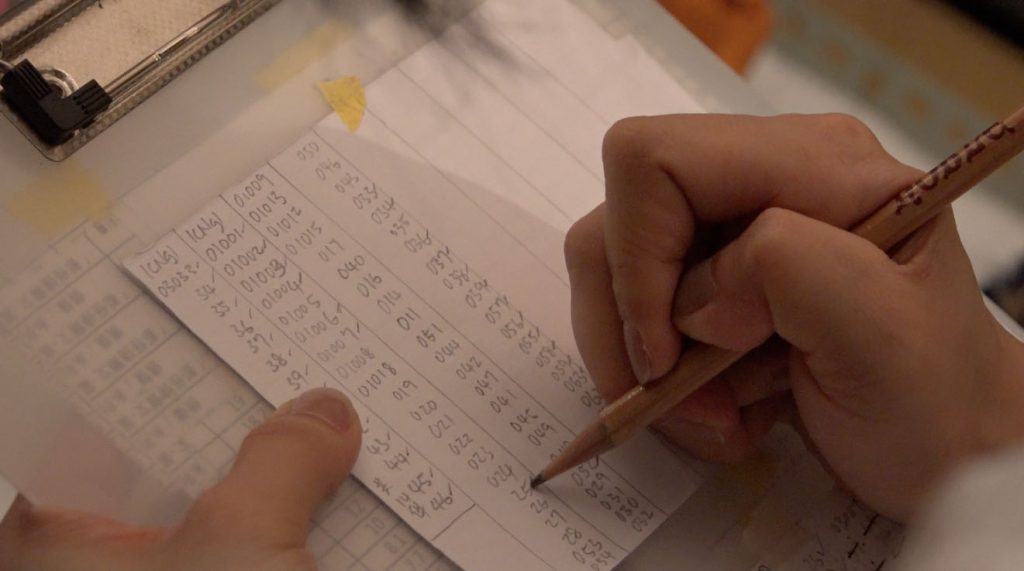

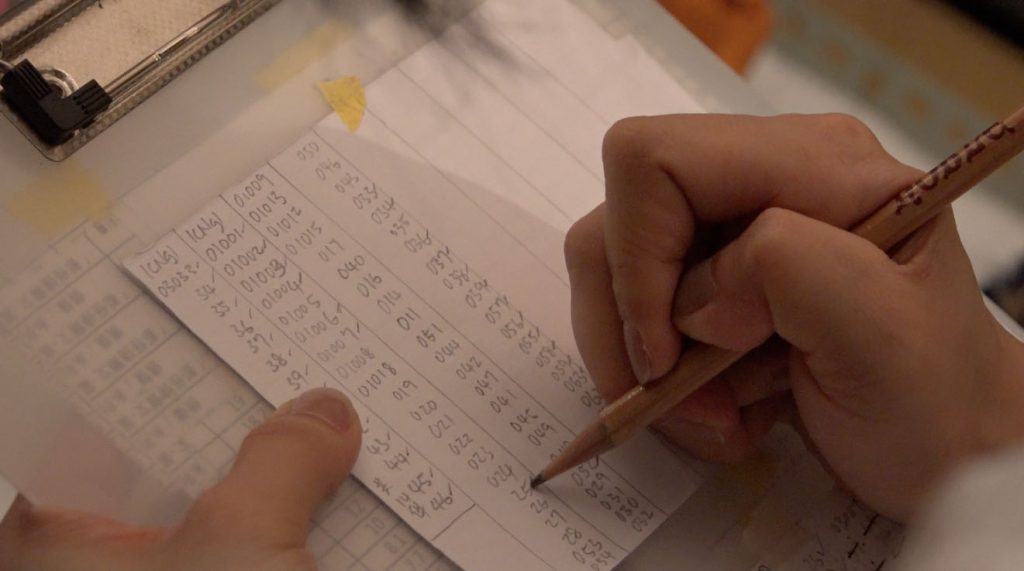

There is Robin’s list, which is the primary list, then there is somebody from the museum who is going to the shelves and checking that list against the shelf experience and seeing that every object is numbered and allocated where it should be, and sometimes she finds anomalies. So that’s what I was just photographing now, there had been some rods that had been missed, so she draws up the primary list for the packers, so she hands her list to the two who are doing the number checks, and what’s happened is that beautiful little partnership that you are observing, the packers are cooperating so sweetly with the two that are checking. The one person is checking against the list and they are also identifying which box number is absorbing what numbers, so she is checking that. And then the other person is writing a second list for the box, so that she can place that new list on the box itself, so we can identify what’s inside the box. And what’s so sweet is that the packers are also working with them as they are checking, so they exchange and call out numbers to each other, so that process is mediated in a good way. And then I come along and I put my stamp on to say that that process is complete and checked and sound. That was the orange label that correlates with the number on the box.

Talking with Kim we wondered:

How do you generate the first set of numbers? What are the originals? What are the “ur-numbers” that generate that avalanche of lists that come after them?

eteam: I would like to return to the book that you wrote while you were working with this collection as a conservator. You could have written a book in words, but you wrote a book in numbers. Can you tell me what the book is about?

Kim Siebert: There are a few of these notebooks and when we started we had a file of loose sleeves and then we realized, it’s best to just have it in a bound book. It’s just a very simple book, and here we are going through the collection, we checked the whole collection before the transfer to the Taiwan National Museum, and you can see here for example, the first number is “Chinese Glove Puppets” CN is Chinese and GL is Glove Puppet, and as you an see here I have gone into sequencing here, and then I include the height or length, the widths and the depth of the object and then sometimes we have included the weight. And so there are just pages and pages and pages of us checking things in the inventory. And a lot of these were for example piles and piles of say: sticks. So, some of them are very interesting and diverse objects and some of them are very similar objects of the same type, so it’s just pages and pages and pages, and then there are more books than this. Some of these were already accessioned, we had this data in the collection, but there were some things that we had not accessioned, particularly shelves of shadow puppet rods for example, but in the transfer we had to give them each a number.