Again, we went back to the Taiyuan Asian Puppet Theatre Museum and observed how the art handlers were packing up the individual objects of Dr. Paul Lin’s collection, which contains about actual 8000 puppets. May be it was the neon light on the white paper in combination with the blue sterility of the gloves, may be it was the professional way, the packers lifted up the skirts and robes to search for the ID tag, may be it was the room brimming with human voices calling out and crosschecking ID labels, may be it was the increased speed, with which the workers, now behind schedule were packing up… at one point, as we held our camera high above the packing tables and watched as puppet after puppet was wrapped into white paper, labeled, put into a metal shelf, and then into a cardboard box, we began to think of body bags for the dead and began to realize that the mix of human features, hairstyles, make up, expressions, upkeep, ages and sizes that was processed on these tables made us miss being in NYC among New Yorkers.

In April of 2020, about a year ago, as the virus strained funeral homes, NYC employed more than 45 temporary, mobile morgues. Since then more than 30.000 people have died from the Corona virus in NYC alone since the start of the pandemic, which made us wonder how watching a small portion of 8000 puppets being wrapped up would relate to watching 30.000 people being put in bodybags and coffins – just in terms of time needed to do that. How did the people working in the hospitals and morgues handle the sheer numbers? How long did and does it still take to practically “process” the dead of the pandemic and how long will it take to spiritually “process” this incredible loss?

We wanted to pause and say: Puppets don’t decompose very fast. This needs more time. The puppets need a ritual. A priest. Some joss sticks. Someone needs to close their eyes before they are being put into this climate controlled storage vault. A blindfold. It does not feel right to crunch up a piece of paper and push it onto their faces for protection.

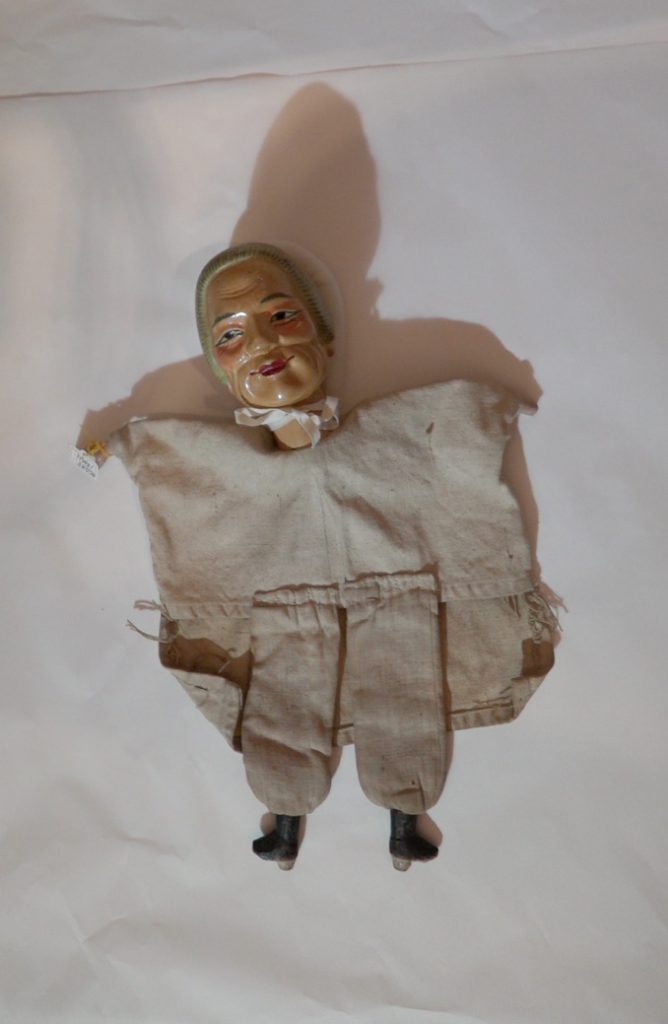

Eventually this smiling, elderly female puppet appeared on the table. May be because she was “naked,” may be because she looked “good natured,” may be because she spread her arms “like inadequate” wings trapped between being and inanimate object and a living being, may be because as part of a museum collection she was already part of an archived history, something about her made us think about “Angelus Novus,” this painting by Paul Klee about which Walter Benjamin wrote in 1940, the same year he committed suicide while trying to flee the Nazi regime:

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.[1]