Handheld storytelling devices are controlled via skills in the form of movements or gestures. These movements have emerged, been developed and refined to exploit the size of our palms as support platforms, flexibility of our joints and the versatility of our digits. Learning skills is accomplished by following or copying instructions, cultural, visual, audible or written. A learned skill is a copy of the original. Some of the skills humans have acquired through life experience and evolution are referred to as natural gestures. These are mostly simple non-verbal hand gestures such as: “wave”, “slab”, “grab”, “point”, “pull”, “swipe”, … and are used in inter-human communication for non-vocal interaction or in inter-species communication as signs, commands or forced movement (grabbing something, pushing something, pulling something, …) User interface and user experience designers of digital devices have developed “natural” gestures to make learning and adoption of their designed device controls easier and more acceptable so we are then able to tell new stories. Conscious stories we compose by operating the handheld devices as instructed.

Natural User Interface (NUI) Gestures

“Until now, we have always had to adapt to the limits of technology and conform the way we work with computers to a set of arbitrary conventions and procedures. With NUI, computing devices will adapt to our needs and preferences for the first time and humans will begin to use technology in whatever way is most comfortable and natural for us.” —Bill Gates, co-founder of Microsoft

Instead of improving their own abstraction and skill learning, natural gestures now enable humans to treat devices as adolescent entities in need of education on how to best serve us. The goal of NUI according to Bill Gates is: “…to use technology in whatever way is most comfortable and natural for us.” Wikipedia states that “An NUI relies on a user being able to quickly transition from novice to expert. While the interface requires learning, that learning is eased through design which gives the user the feeling that they are instantly and continuously successful.” Speed is emphasized in this definition of NUI’s as the user quickly transitions from novice to expert while feeling instantly and continuously successful. Failure is not an option in continuous success.

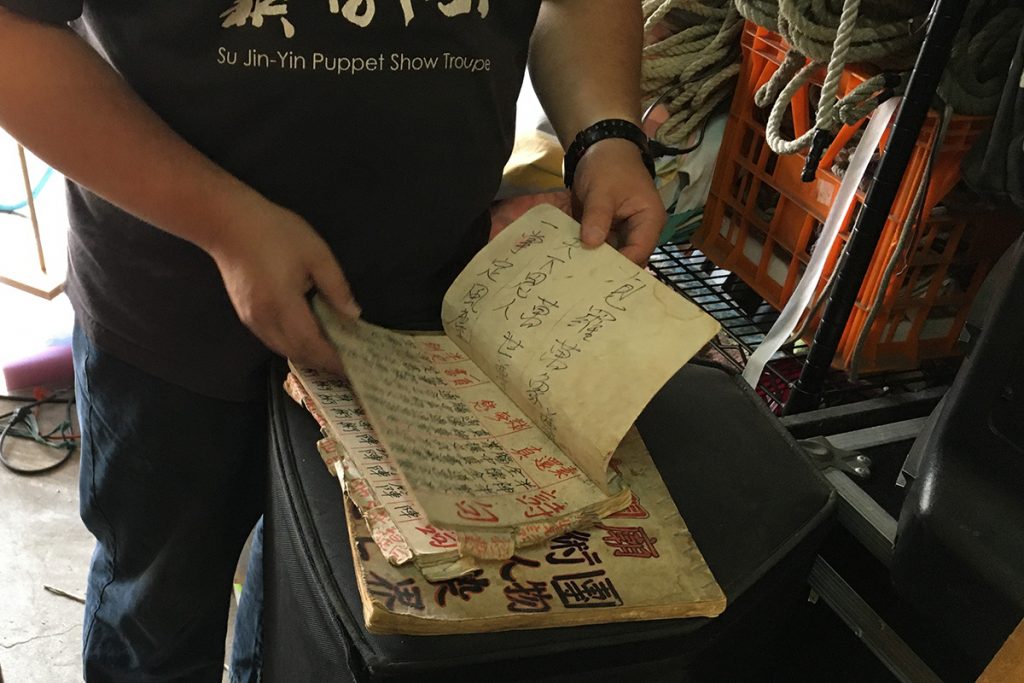

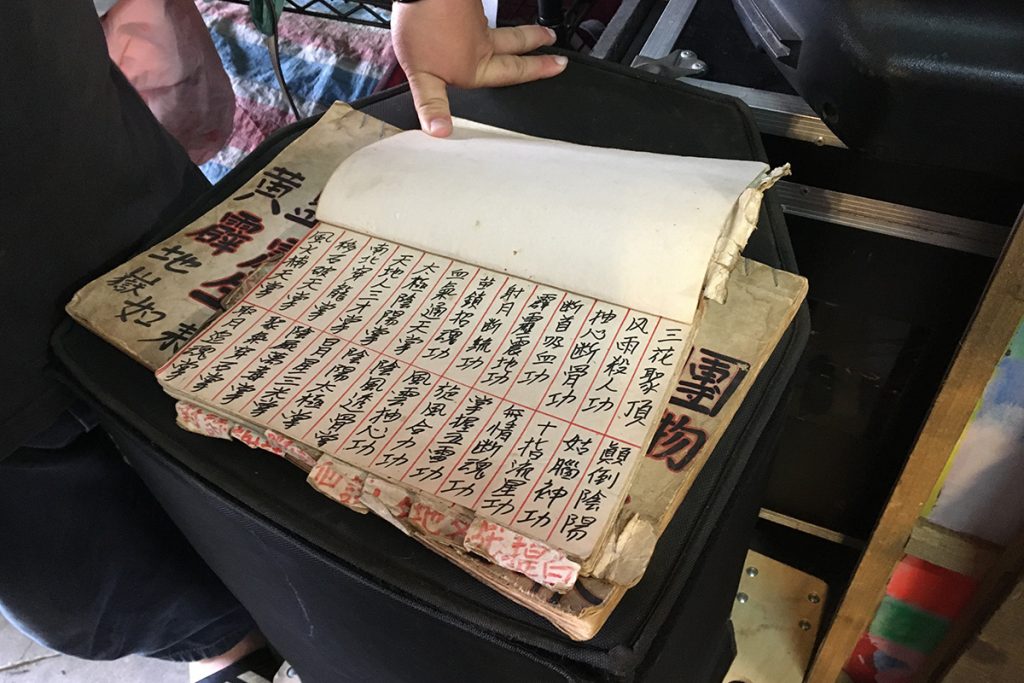

In traditional Budaixi (布袋戲, also sometimes written as potehi or poteshi), knowledge and movement has been taught and learned in master disciple relationships, where practice, failure, mistakes and feedback are leading to improvement. Lucie Cunningham has spent 5 years as a disciple of Master CHEN Hsi-huang in Taipei and says about her experience and the process of learning to control hand puppets “the hardest was to learn the movements“.

In traditional Budaixi (布袋戲, also sometimes written as potehi or poteshi), knowledge and movement has been taught and learned in master disciple relationships, where practice, failure, mistakes and feedback are leading to improvement. Lucie Cunningham has spent 5 years as a disciple of Master CHEN Hsi-huang in Taipei and says about her experience and the process of learning to control hand puppets “the hardest was to learn the movements“.

🤳 🖖 🖐 ✋ 🖐 🖖 🖐 ✋ 🖖 🤳

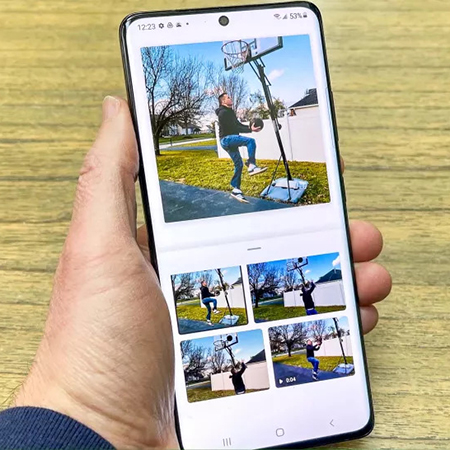

Considering the handheld computing device as a hand puppet, its operation is simplified or “naturalised”, and its smart processing power makes up for the hardship of learning skills* when compared to traditional puppetry. This built-in processing power allows these new puppets to tell new stories and demonstrates a new form of storytelling embellished by the interpretation of the machine. In Bill Gates words: “…computing devices will adapt to our needs and preferences for the first time…” as such one can conclude, they will be able to compensate for our shortcomings.

The traditional story

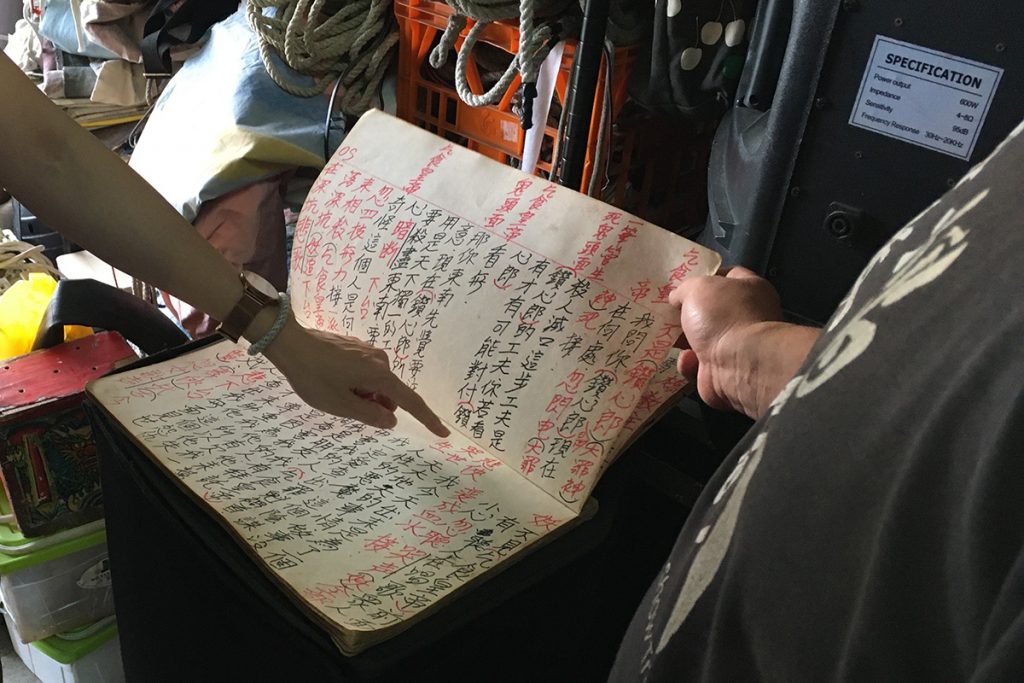

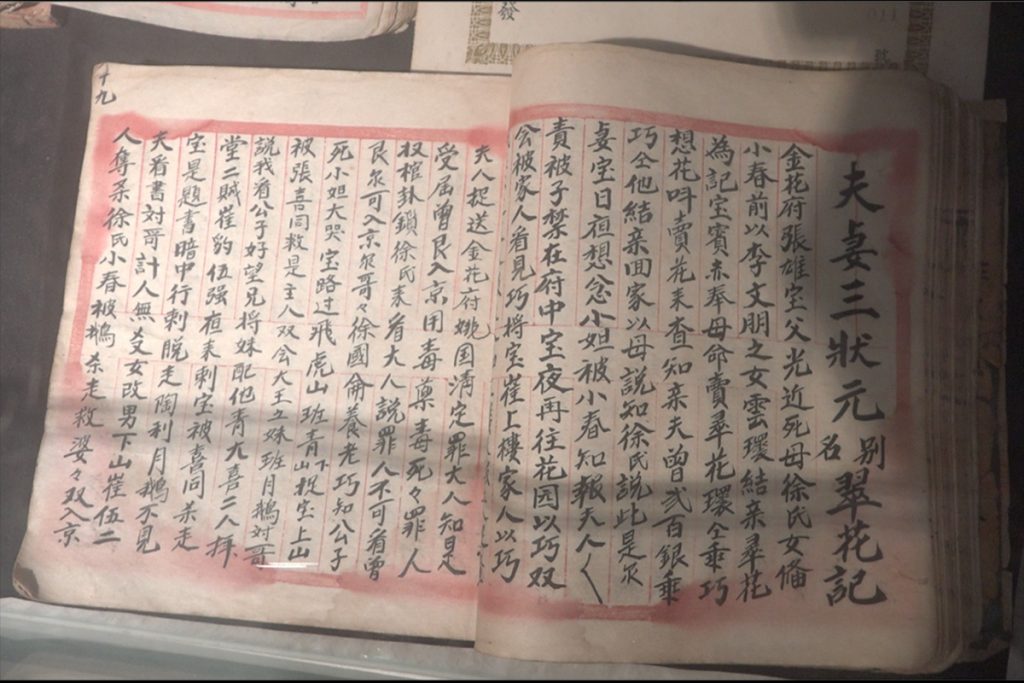

Traditional Budaixi is performing stories that have been written into books and are handed down from one generation to the other. Alvin P. Cohen writes in A Taiwanese Puppeteer and His Theatre: “(He) also learned many stories (upon which puppet plays were based): Some from books, some told by the master puppeteer, and others that he made up himself. Mr. Luh stated that about half of the stories were on ” historical ” themes and half contemporary” themes.” These stories can be narrated by a single narrator or each puppeteer can give their voice to an individual character.

In addition to the narration, these stories are enlivened by the puppets through the hands of the puppeteers. How close the puppeteer and narrator is following the story depends on the occasion as Mr Su Jin Yin of 蘇俊穎木偶劇團 and Mr. Li from the 真雲林閣掌中劇團 troupe both stated in interviews with us. For performances in theaters everything is scripted and there is no room for improvisation unlike in temple performances where improvisation plays a huge part – which both Mr Su and Mr Li enjoyed more. Especially when the performance is competing for audience attention in a temple fair, JinGuang (金光布袋戲 ) performers need to be able to capture audience attention and have found spectacular and effectful ways to draw attention.

The digital story

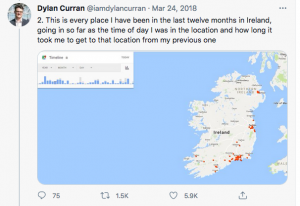

The stories we compose, perform and distribute using digital handheld devices take different forms. Longform social media narratives where the narration bridges locations, mixes characters and provides connections in textual form and friendship. Shortform narratives in the form of live streams, “events”, “stories” and “TikToks”. The audience for our digital stories is in most cases invisible to us except for voluntary tokens in the form of a “Thumb up”, Thumb down”, “Like”, “Heart” or other representative emotion. Those tokens and play metrics for videos are perhaps the only signs of an audience unless there is a comment proving further presence and engagement. But there is also an audience for the digital stories we constantly compose and don’t intend to distribute. These are mostly unedited narratives that we create often unconsciously in the form of data. Data which captures and stores our moving digits to improve our user experience. Data which captures our geographical movements to propose places of interest.  Data which captures our interest to propose things we might find relevant. Data which captures our search and browsing history to predict what is best for us. Data which captures our usage habits to suggest traffic, shopping or food options. What differs dramatically in these stories is the audience. Stories we compose consciously have no known audience, we compose them in the hopes or assumption they will be seen, read or heard by a human audience that isn’t us, the author. Data collection story audiences are firstly machines which evaluate the story for its success or usefulness to turn the storyteller into the audience of their own story. The machine becomes a ghostwriter suggesting future plot lines and composing these digital short stories into chapters and a larger manuscript assigned to an anonymous author and to be pitched to a pool of publishers or resellers.

Data which captures our interest to propose things we might find relevant. Data which captures our search and browsing history to predict what is best for us. Data which captures our usage habits to suggest traffic, shopping or food options. What differs dramatically in these stories is the audience. Stories we compose consciously have no known audience, we compose them in the hopes or assumption they will be seen, read or heard by a human audience that isn’t us, the author. Data collection story audiences are firstly machines which evaluate the story for its success or usefulness to turn the storyteller into the audience of their own story. The machine becomes a ghostwriter suggesting future plot lines and composing these digital short stories into chapters and a larger manuscript assigned to an anonymous author and to be pitched to a pool of publishers or resellers.

The new form of data collection story in which the author becomes an actor and where a machine audience is digitally processing the story and giving directions to the actor/author is complicated and messy as the story is ongoing and constantly developing.  What happens to the author who is acting, when slowly there are more stories to reenact than those that had been created by a singular human organism? Is the actor overwhelmed? Is the actor going on strike? Is the actor surrendering to the machine, becoming a machine? Is the author loosing the author status, giving up authorship and becoming an actor without authorship? Especially if the story the actor is now following is presented by a biased algorithm which encourages homophilic behavior to make the path of the story-line as effortless as possible. “Homophily in personality may reduce cognitive load: if other individuals act and react similarly to oneself, less cognitive effort has to be spent in predicting their behavior 1“. Arrival at this state eases stress on the actor. If the new machine-author has led the author-actor to this point, it can consolidate the different stories and promote just one.

What happens to the author who is acting, when slowly there are more stories to reenact than those that had been created by a singular human organism? Is the actor overwhelmed? Is the actor going on strike? Is the actor surrendering to the machine, becoming a machine? Is the author loosing the author status, giving up authorship and becoming an actor without authorship? Especially if the story the actor is now following is presented by a biased algorithm which encourages homophilic behavior to make the path of the story-line as effortless as possible. “Homophily in personality may reduce cognitive load: if other individuals act and react similarly to oneself, less cognitive effort has to be spent in predicting their behavior 1“. Arrival at this state eases stress on the actor. If the new machine-author has led the author-actor to this point, it can consolidate the different stories and promote just one.

The numerical story

We use our hands to tell stories, but the gestures and stories are not always identical. One of the most universal and simplest story our digits can tell might be 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Yet the way this story is told in different geographical regions of the world varies greatly and has a different reception the moment it isn’t comprehended in its linearity anymore, the moment the characters of the story no longer have the same name or value for every viewer.

According to research by the mathematician Yutaka Nishiyama, published in COUNTING WITH THE FINGERS , “In the West, the thumb represents 1, but in Japan it indicates ‘man’. In the Philippines, the little finger represents 1, but in Japan it indicates ‘woman’. ”

So a simple story of two thumbs up ![]() could indicate full support/well done, be a double 1 or two men and probably much more. Turning the hand 90 degrees and adding a little finger

could indicate full support/well done, be a double 1 or two men and probably much more. Turning the hand 90 degrees and adding a little finger![]() a love story could unfold for a Japanese recipient or read as a six for Chinese eyes.

a love story could unfold for a Japanese recipient or read as a six for Chinese eyes. ![]()

Any good story should begin, according to writer and educator John Gardner, by “... either a trip or the arrival of a stranger (some disruption of order—the usual novel beginning). …

Can numbers represent disorder? If numbers are represented by signs like the above mentioned example of counting with ones fingers, then mixing the representative signs would create a visual disorder. If numbers are represented in a uniform Hindu-Arabic format there could be random lists of numbers which don’t follow a discernible pattern thereby creating chaos. But what about zeroes and ones? How much disruption is possible? o,1,0 or 0,0,0 or 1,1,1 or 1,0,1 How much turmoil or disruption can be shown by zeroes and ones, two digits alone? On and off.

So it’s back to the 10 digits to disrupt the order to create a better beginning, getting our genetic digits take the lead over the digits assigned to us by non-genetic code. 👍

Or are semi-conductors the magic disruptors between 0 and 1?