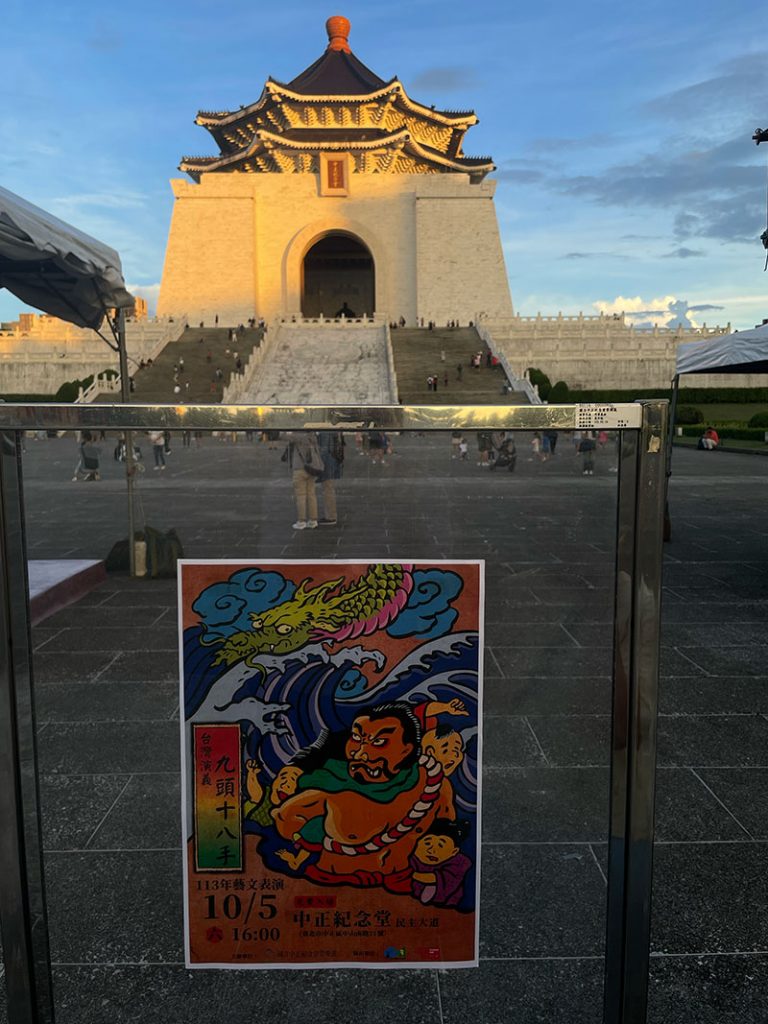

When we, on Saturday, October 5, 2024 at 4:03pm rush around the massive white building with the octagonal blue roof, we first see – situated under a temporary tent about 100 meters in front of the double set of 89 stairs that lead up to the 44 years old, 6.3 meters high, bronze statue of Chiang Kai-chek – the back stage of the puppet show. Three black clothed puppeteers squeeze themselves around the small openings in the upper part of the puppet stage, their hands are up in the air, their feet are stomping audibly onto the wooden boards. Right behind them is a folding table with piles of puppets on the ground sits a smoke machine. To the left stands a big black loudspeaker on a tripod. Behind that, under another portable tent, sits a woman who operates a laptop and a black box with 28 big, red buttons, which she pushes to trigger music clips and sound effects, that punctuate whatever stabbing, flying, running, crashing, dreaming, crying or tumbling action is going on in front of the stage. The sound effects are loud, the live narration and dialogues, mostly performed by Mister Li from the 真雲林閣掌中劇團 Zhen Yun Lin Ge Glove-Puppet troupe through his clip on mic, are loud, the pop songs are loud, the Western movie soundtrack imitations are loud, the laughing roars and the crying weeps. The presence of the soundscape, which turns the puppets into much bigger versions of themselves, gives us a flashback to an educational wall label in the Dadaocheng Theater 大稻埕戲苑 that explained: “As they say in show business: Three tenths front stage, seven-tenth back stage.”

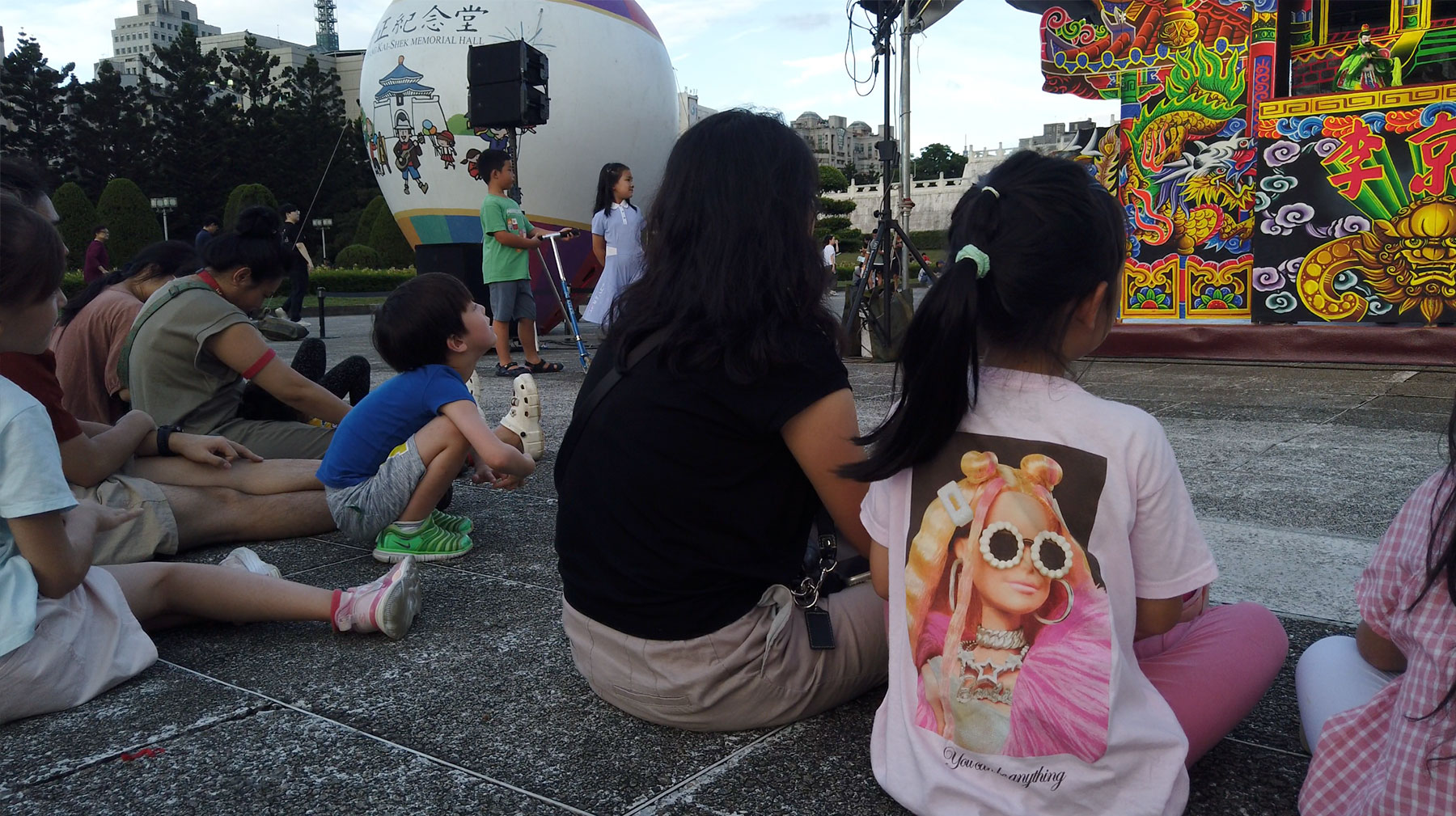

We slowly walk towards the front of the stage, happy to see so many people sitting on the ground; families with small children, teenage couples, elderly people standing on the sides, some are holding up their smart phones horizontally filming the show. We keep walking and stop at the magic side point, where our perspective condenses the puppet stage into a thin, vertical line. To the left from this line sits the audience, people who smile, yawn, laugh or clap their hands. To the right of the line stands the table with the piles of puppets, pieces of colorful cloth with wooden heads, ready to be animated and brought to life, the moment the puppeteers slip their loving hands into their dead and hollow shells.

Back. Front. Everything is out in the open, we think, and have another flashback to the many instances where we marveled at the fact, that many restaurants and eateries in Taiwan cook their food in outdoor kitchens on the sidewalk. As you walk along the sidewalk you look left at what is being washed, poured, chopped, mixed, stirred and cooked by whom and how, and then you look right at the dining room situation, the food’s final presentation in bowls or on plates, the light situation and the other people who sit on the tables. And then you either decide to eat there, or you move on.

We keep walking forward and find a spot in the last row of audience members. Having the grand overview and not understanding the language of the performed story, gives us a chance to contemplate this particular setup of the stage in relation to the massively elevated Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial and compare it with a traditional temple performance. In order to honor and entertain the gods, spirits and deities the front of the puppet stage always faces the small statues of deities and spirits housed inside the temple, while this situation bluntly turns its back towards worshipping authoritarianism.

Just a few weeks earlier, in July of 2024, Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture moved the “changing of the guard ceremony” from inside the memorial hall to the outdoors, therewith publicly implementing the current government’s agenda that “eliminating worshipping a cult of personality and eliminating worshipping authoritarianism is the current goal for promoting transitional justice.”

When it becomes available, we hunch, bend our knees and apologetically hurry towards the empty spot in the second row right in front of the puppet stage. This not only brings us close to the puppet action, but also makes us realize that from this perspective, the Ministry of Culture’s efforts to stop the promotion of the cult of personality around Chiang Kai-Chek, fully succeeds. The foldable, quickly erected, brightly painted, wooden puppet stage completely covers the view of the massive memorial hall behind it, which took five years to build.

The performance, called “Nine Heads Eighteen Hands” is performed in Taiwanese Hokkien, and relates meaningfully to the site. After the Chinese Civil War, when Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang (KMT) retreated to Taiwan in 1949, the KMT started promoting and enforcing Mandarin Chinese as the official language and issued laws requiring all Taiwanese to speak Mandarin, which led to resentment among the Taiwanese, who had previously spoken Hokkien and other regional dialects. There were outbreaks of rebellion and clashes with military police.

Mr. Li, who lives and works in Yunlin County came about the legend of “Nine Heads and 18 Hands,” when he researched the origins and life of a deity in a temple near his house. Before this deity became a worshipped deity, he was a local man who jumped into rescue action during a terrible flood. In an effort to save themselves, eight children climbed onto his back turning his body into a being with “Nine heads and 18 hands.” All drowned, yet the man’s heroic efforts turned him into a spirit in whose honor the temple was erected.

It’s a tragic, continuously fourth wall breaking, funny, slapstick, melodramatic, sad, humbling story performed outdoors in a highly charged historical setting accompanied by a dramatic sunset in the sky, a pleasant wind flow and lots of local and international tourists moving around. The moment the show is finished, a pair of grey clothed honorary military guards marches from the mmorial hall towards the flagpole, followed by a large crowd of people. They all assemble around the pole, some with their hands on their hearts. The military guards ceremoniously lower the flag of Taiwan for the day and the puppet troupe members pack their belongings into a small grey van. They all leave Liberty Square, while the sun sets behind The National Concert Hall.

Thanks to 真雲林閣掌中劇團, especially Li Jing Ye and his assistant Jaimie who translated our brief post-show conversation. The poster was painted and designed by the puppeteer to the right.

Thanks also to: Fulbright Taiwan – Foundation for Scholarly Exchange