On October 9, 2024 we met with 楊雨樵 Yang Yu-Chiao, a full time performer and independent writer of oral traditional folktales, who also does research on narratology, story poetics and comparative storytelling in oral literature, drama and film. We talked in his studio at Taiwan Contemporary Culture Lab 臺灣當代文化實驗場 C-LAB, where he currently is an artist in residence to work on: “The House of Onomatopoeia – Residential sound Collecting, Writing and Articulation Project”.

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines Onomatopoeia as the naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated by it (such as buzz or hiss), and cites Christian Marclay who said: “In comic books, when you see someone with a gun, you know it’s only going off when you read the onomatopoeias.”

We wanted to talk with Yu-Chiao, because we have been wondering, why we enjoy watching Taiwanese Puppet Play Performances or Taiwanese Opera Performances without understanding the actual language of the plots. Is it satisfying being led through performed emotions of suspense, excitement, melancholy and humor without understanding how exactly we are relating to these feelings? Is it liberating, mind opening to understand the story outside of its plot?

A long, long time ago, there was a little story who sat in the shade of an old, tall tree keeping its characters cool. A group of storytellers came along, and attracted by the story’s diamond like beauty, each one wanted to own it and put it into their pockets. “No,” said the little story, “the way you own me is by attaching a storyline to my core. Get out your yarn!” And so they did. They knotted their yarn around the story’s core and all went off into different directions…bang, bang, bang, bang, bang….

Our conversation with Yu-Chiao meandered into many directions, but the question we always returned was this: What are the methods and techniques being used in folk tale telling, that transmit something from the content of the story without having to rely on the language?

Firstly, Yu-Chiao confirmed, that folk stories can be understood outside of the verbal language domain. As examples he mentioned several occasions, where he had told Taiwanese folk tales in Mandarin to audiences in Korea, Sweden and France. After all performances the children said, they had understood. Not everything, but most.

This, Yu-Chiao explained, might be a built-in characteristic of folk tales that developed over long periods of time. Traditionally folk tales were often told by business-men, who traveled from place to place to trade in goods. The tales they told were not translated, so audiences from different cultures who spoke different languages learned to understand by guessing fragments of the story, by feeling emotions, and by becoming familiar with a certain formula of story-telling. First is the structure, then comes the plot. The plot, Yu-Chiao explained, takes on the formula and proceeds with it, the plot takes on the formula and drives it forward.

In terms of formulas, Yu-Chiao explained, he thinks about the oral-formulaic theory in Anglo-Saxon poetry, also known as the Parry-Lord theory. It is a compositional model, developed by Milman Parry (1902–1935) and Albert Lord (1912-1991) that explains the creation of oral epic poetry and takes identifies principles, such as Formulas: Repeated groups of words, often with a specific metrical pattern, used to express a particular idea or concept. Traditional Patterns: A shared stock of formulas, themes, and narrative units inherited by oral poets from their tradition, which are not individual creations but rather a collective cultural heritage. Oral-Formulaic Composition: The process by which oral poets generate poetry by drawing upon their internalized traditional patterns, including formulas, themes, and narrative units. Grammar of Poetry: The internalized rules and conventions governing the use of formulas, themes, and narrative units in oral poetry.

Implications of these concepts speak to Orality: The Parry-Lord theory emphasizes the oral nature of epic poetry, highlighting the importance of performance, improvisation, and audience interaction. Collective Creativity: The theory suggests that oral poetry is a collective endeavor, with poets drawing upon a shared tradition rather than individual creativity. Flexibility and Adaptability: Oral-formulaic composition allows for flexibility and adaptability in response to narrative and grammatical needs, enabling poets to improvise and modify their performances.

Secondly, Yu-Chiao explained, folktales often include some sort of sound secret within the language itself. Part of that secret is called onomatopoeia, the use of words that phonetically imitate or resemble the sounds they describe, like buzz for bees, grrrr for being angry or booom for loud sounds. Traditional storytellers use hundreds of them in their tales.

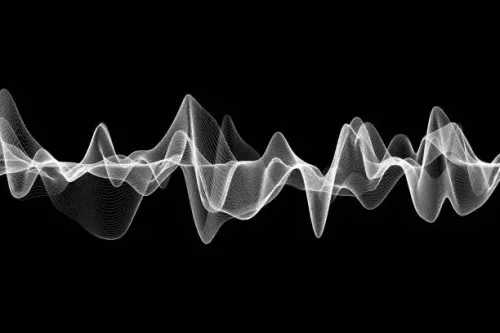

Thirdly, there is the use of a beat, a rhythm. It can be hand clapping, or knocking on the table, it can be a bamboo stick hitting wooden fish, it can be the ringing of a bell or the hitting a gong.

Yu-Chiao first linked the use of percussion instruments to creating an atmosphere and further explained, that they are a convenient way to control the tempo. “The drums are like the heartbeat of the story.”

With that we had already identified three techniques. We got the story formula and our familiarity with its patterns, we got the onomatopoeia, mimicking real objects or feelings through sounds and we got the heartbeat of the tale, which drives us forward with its rhythm, but isn’t there more?

What about the stretching of the words? Like Ooooooohhhhhhhh, my heart huuuuuuurts baaaaaheeeaaaadly.

Like Gregorian Chanting, Yu Chiao asked? Yes, like Gregorian chanting, or Buddhist chanting, or tragic songs in Taiwanese, Beijing, Italian opera ….any sort of practice or performance, where words become longer and longer and longer, we said.

When we speak in daily conversation, Yu-Chiao explained, we use the words like compressed files. We say them, we understand them and that’s it. We have exchanged some information, and when you tell a story very quickly it goes like this: A long time ago, there was a princess, she married a prince, and they lived happy together until they died. The End. You got it, but it doesn’t mean much.

Yet, when the storyteller releases the words into the atmosphere by stretching them out, the listener will discover that the words carry something else but their meaning. We know from symbolic theory, Yu-Chiao explained, that there is the signifier and the signified. The signifier is the sound, the shape, the outline, the material, which gives us clues that – ohhhhh —– maybe something else is the meaning. The sound is the way to the meaning, but not the meaning itself. So, when you stretch the word into a sound, the sound, will be independent from the word. Suddenly there exists more than the word.

—–

If you want to find out more about Yu-Chiao’s work you can check out the following links:

The house of Onomatopoeia, No.2 https://youtu.be/fOd2Vf4Dg8I

Blackboard Scribophone (in South Korea) https://youtu.be/c9nXByeDEPI

Mille Sonos- Anamorphosis & Anatexis https://youtu.be/arYoMAGULN4

Thanks to:

楊雨樵 Yang Yu-Chiao

Taiwan Contemporary Culture Lab 臺灣當代文化實驗場 C-LAB

Fulbright Taiwan – Foundation for Scholarly Exchange