Many puppet troupes perform for different purposes and what keeps us interested in attending their shows, is not only to become aware of the wide variety of stories being performed in different styles, but also to observe how the puppet performances adapt to various environments and types of audiences.

Who are these audiences and how do they perceive a performance under what conditions?

In this post, we’ll try to describe three scenarios: Theaters, Schools and Temple Fairs.

Theaters:

Quite a few puppet shows happen in black box theaters. These shows are being advertised as part of the theater programs and tickets are being sold in advance. Audience members arrive at a given time and depending on how much they paid, they will sit in assigned seats closer or further away from the stage. Moments before the show will start, the doors are being closed, the lights are being dimmed and a recorded voice announces that “eating, drinking, smoking, photography and videotaping are not allowed.”

The theater performances are choreographed collaborations between puppeteers, musicians, light and sound-designers. They typically adhere strictly to their scripts, leaving little room for improvisation. The darkness of air-conditioned, sound-proof rooms aids to focus the audience’s attention onto the stage, remaining physically still and silent, except for laughter or clapping their hands.

After the conclusion of the show, the house lights come on and the audience becomes visible together with the puppeteers, who who take a bow in front of the puppet stage, possibly together with the musicians. The audience responds with applause before making their way to the theater lobby, where the puppeteers, with puppets on their hands, will encourage them to take group photos to memorize the occasion.

Educational Institutions:

Puppet shows designed for children in elementary schools or other educational institutions form a significant part of many troupes’ income. These performances, typically held in school auditoriums are mostly funded or subsidized by Taiwan’s government. The current focus of these initiatives is to familiarize children with aspects of Taiwan’s intangible heritage, such as traditional Taiwanese puppet theater, exposing them to the Taiwanese language, teaching specific words in Taiwanese or Hakka (as distinct from Mandarin), and sharing stories or legends rooted in Taiwan’s islands rather than in China.

We accompanied the Taipei Puppet Theater 臺北木偶劇團 to several of such school outings and while it was entertaining to watch parts of the puppet show from the audience’s perspective, it was equally fascinating to switch our vantage point, hide behind the stage and observe a brimming auditorium filled with rows of captivated children, which actively responded to either the puppet show or the main actor’s performance – a human called “monkey brother” – in front of the stage.

Loud, roaring laughter is definitely contagious (we surely don’t have a defense mechanism) and spreads incredibly fast through a room of a hundred children. Yet, why did the children laugh?

There are many theories, why humans laugh and many standards of what people find funny, yet three main theories appear repeatedly in academic literature.

- The “Relief Theory” suggests that humor is a mechanism for pent-up emotions or tension through emotional relief.

- The “Superiority Theory” follows the idea that a person laughs about the misfortunes of others, because they assert their superiority based on the shortcomings of others. Plato described this sort of laughter as being both a pleasure and pain in the soul, and we could definitely observe these mixed emotions —either in the fast changing complexity of an individual’s face, or within the components of this roaring social creature called the audience. Wide, open eyes brimming with surprise or excitement, furrowed eyebrows that signaled confusion or concern, wrinkled noses hinting at amusement or distaste, radiant smiles of joy, jaws dropping in astonishment, stoic stares of deep focus, exaggerated expressions of disbelief… it all intermixed.

- The “Incongruity Theory” suggests that humor and laughter arise from encountering something unexpected or out of place compared to what is considered normal. Immanuel Kant’s version of the incongruity theory defines humor as “the sudden transformation of a strained expectation into nothing.” In his theory, laughter arises from the built up tension towards a cognitive dissonance. The philosopher Henri Bergson who published Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (1900) remarked that we are able to laugh at non-sentient things only under the condition that we discover something human-like in them.

“You may laugh at a hat, but what you are making fun of, in this case, is not the piece of felt or straw, but the shape that men have given it, – the human caprice whose mould it has assumed.”

Although laughter and humor are profoundly important social phenomena—and may currently serve as valuable indicators of how “humanly” we perceive AI or ChatGPT when we find their jokes funny—we’ll use the quote: “that there is something unnatural about subjecting one of the most pleasurable and ubiquitous human experiences to dry philosophical speculation,” from Emily Herring in Laughter is Vital, to approach the subject more practically and ask Wu Sheng-Chieh 吳聲杰 , the lead puppeteer from the Taipei Puppet Theater: “What are the conditions under which laughter mostly appear and thrive? How do you get the children to laugh?”

Temple Fairs:

A third category for Taiwanese puppet performances are temple fairs, festive gatherings that happen around Taoist and Buddhist temples to honor, celebrate and worship the deities, gods, spirits and immortals who are enshrined inside the temples.

Often these fairs happen around Chinese New Year or on the birthdays of the gods. Depending on a temple’s traditions and financial situation the festivities can include performing of rituals inside the temple, processions of deities around the neighborhood, blessing of offerings or performances by dance troupes, opera troupes or puppet troupes, which take place to entertain the gods on these specific occasions.

A temple fair can last many days, which means performances happen many days in a row, traditionally twice a day. The first show, which usually starts in the afternoon around 3pm is called 扮仙, “Playing fairy” or “Pretending to be fairies,” or “Dressing up as immortals,” an important opening scene/ritual in the traditional Chinese opera and puppet performance culture. 扮仙 is an auspicious play, and the characters that appear on stage, such as the common three immortals of fortune, wealth and longevity, have symbolic meaning that express the people’s prayers to the gods. 扮仙 is sacred in the religious beliefs and folk opera customs in Taiwan, and when invited by a temple, a traditional puppet troupe will always perform this play before the main performance.

The first time we witnessed the performance of such a 扮仙 was when, in April of 2021 a few days before Taiwan went into pandemic lockdown, Su Yin Jin from the 蘇俊穎木偶劇團 performed one in Tainan. We had started the day interviewing Mr.Su and his partner in his house and studio and after lunch went to the 善化慶安宮 (Shanhua Qing’an Temple) where Mr. Su’s stage was already set up.

It was a very hot afternoon. Several large, red and white striped tarps covered the plaza in front of the temple and from their metal frameworks hung rows of electrical rotating fans next to red and yellow paper lanterns and red paper cuts, which fluttered in the artificially created wind. There was a wooden table with stacks of folded spirit money, an offering table covered with orchids, cans of sodas, dragon fruits, oranges and crackers, a large sedan chair decorated in intricately embroidered tapestries and an array of parked scooters next to several stacks red plastic stools, which indicated, that within a few minutes, this empty plaza could be occupied with hundreds of people sitting on stools. One side of the plaza was lined with mobile food carts on which vendors chopped vegetables, folded dumplings, or washed dishes. The other side was lined with a row of large flower bouquets that stood on pedestals dressed in red flowing fabric, like ballerinas ready to burst onto the stage for a festive dance. From time to time people appeared with joss sticks in their hands and worshipped in front of the temple, a man broomed the entrance area, a woman folded spirit money and in intermittent intervals some firecrackers went off in a wired metal can.

Mr. Su’s brightly painted stage was set up right next to the entrance of a liquor store owned by his mother, who appeared briefly to place three smoldering joss sticks on a green plastic stool inside the tightly packed backstage area, where Mr. Su was hanging a row of puppets on a sort of cloth line behind him. Once the puppets were in place, he inspected each one – some puppets needed to have their hair combed, some needed to have their head dresses fixed, some needed a brush down of their clothes. This routine was followed by a soundcheck. The music, as well as parts of the dialogue for the performance were played back from a pre-recorded sound file on a laptop, while other parts of the dialogue and most of the singing was live performed by Mr. Su, who knew the lyrics by heart. His voice was amplified by a microphone affixed to the lower part of the stage, connected to a set of loudspeakers.

If there was an exact moment when the soundcheck transitioned into the performance, we missed it. Yet, once underway, the performance unfolded steadily at a slow pace. There was little physical action—no fighting or running. Instead, the puppet characters spent much of their time bowing, praying, and conversing. Some, propped up on wooden sticks and more subtly animated by the wind, the brimming of the loudspeakers or by the vibrations of the stage caused by the physical movements of Mister Su’s body, even appeared to linger on stage in quiet contemplation.

Because no people were expected to see the show, no people had come to see the show, and no people casually stopped to watch it. In this way, Mr. Su’s performance reminded us of an opera performance we had seen being performed a few years earlier in Hong Kong in a temporarily erected bamboo theater during the hungry ghost festival for the wandering spirits of ancestors. With this, the experience of witnessing humans honoring the presence of divinities or ghosts by performing a lavish, several hours long opera for them, which initially was highly confusing for us, began to gradually widen and loosen our definitions of “audience” and “presence,” and given a completely new perspective we asked:

What does it mean for something to be? What does it mean for an audience to be present?

Sometimes, the absence of something is the strongest indicator of its presence. Having grown up with several large elephants in the room, we intuitively recognize this as one truth, yet in a world fixated on visual, audible, mathematical, and scientific proof, it can be challenging to keep the doors of this mindset open. During the hungry ghost festival in Hong Kong, when the human opera troupe performed for rows of empty chairs, we reasoned, that ghosts in stories are often described as see-through or non-material entities. Yet, even saying “the chairs were empty” underscored how deeply our recognition of other presences depends on visibility, how little we know about ghosts, and how limited we are in our ability to sense and acknowledge them.

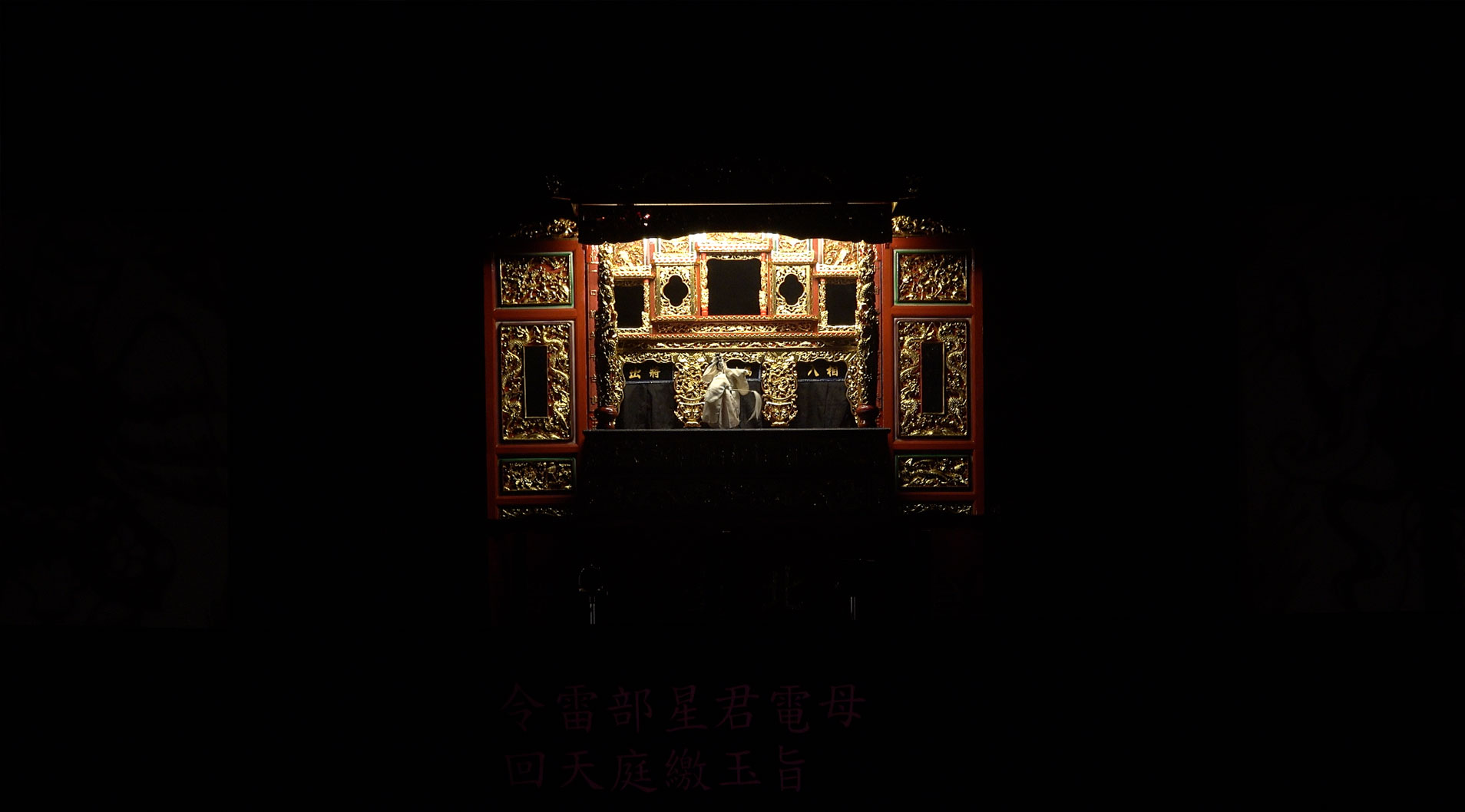

In Tainan, on the other hand, the non-human audience was visibly present. Anthropomorphic statues of the deities and their guardians were lined up on the altar and along the walls inside the temple, however, there was an inconsistency with what we just had learned about entertaining the gods: Mr. Su’s puppet stage, which was supposed to be placed in front of the altar, was not directly placed in the line of sight with the deities, but off to the side. This meant the deities either had the ability to see through the walls of the temple or could bend the path of their gaze around physical obstacles. Both scenarios were plausible.

Of course, a deity’s ability to “see” most likely doesn’t align with the way a human sees along an imaginary straight line between the eyes and an object, unobstructed by barriers. A deity’s vision probably isn’t like wireless signals either, which can be disrupted by walls and other obstacles, which begs the question: Why is the line of sight between the deities on the altar and the puppets on stage so carefully maintained in most traditional temple fairs? Why is it so important for the stage to be placed across from the altar? Why is this arrangement an important part of the tradition of entertaining the gods?

Thanks to:

Taipei Puppet Theater 臺北木偶劇團

Su Yin Jin of 蘇俊穎木偶劇團

and Megan Lan who was our translator during this trip

Fulbright Taiwan – Foundation for Scholarly Exchange